A Staged Theory of Cognitive Development?

Language development is the story of the development of language. Social development regards the development of social interaction. Motor development involves the motor system… What about cognitive development, what is it that humans and animals develop?

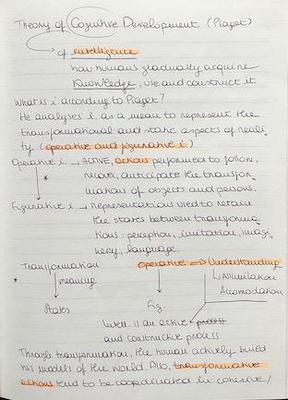

Cognition is perhaps a bit of a non-see-through piece of jargon: derived from the latin word cognitus - literally the past participle known of the verb to know - the noun refers to facts and acquired knowledge. So, we may conclude that Cognitive Development refer to how humans and other animals build expertise and knowledge. However, Cognitive Development has ended up for broadly referring to the development of intelligence, rational thinking, and almost ANY other capability.

Often, charts showing the milestones of cognitive development include heterogeneous skills, such as problem solving, memory, language, and even motor properties. In Jean Piaget’s original formulation, skills across different domains concurrently progress and reach endpoints: mechanisms of change are seen as domain general.

According to Piaget, these heterogeneous skills are just actions and representations used for the same purpose - control the dynamic and static aspects of reality. To do so, an organism - such as a young infant - will develop actions to follow, recover, and anticipate the transformations of objects and people. This set of skills falls under the definition of operative intelligence, whose stage-like progression dominates the first year of life:

1) 0-6 weeks: newborn’s reflexes superseded by intentional actions, such as grasping

2) 6 weeks - 2 months: the infant engages in repetitive actions and develop habits. Passive responses such as operant conditioning starts to occur

3) 4-9 months: thanks to better coordination of vision and prehension, the infant can grasp objects intentionally. Also starts to tell the difference between ends and means, and react to object permanence

4) 9-12 months: the infant start to coordinate means and ends, thus orienting actions to a goal - also called logic

5) 12-18 months: the infant starts to discover myriads of means and becomes a “young experimenter”

6) 18+ months: the infant begins to have insight, entering the pre-operational stage.

In parallel, the young infant will also develop mental representations to retain information about the states of objects and people between transformations, known as figurative intelligence. This set of skills include perception, imitation, imagination and language, defined as figurative intelligence, whose stage-like development stretches to adolescence:

1) Toddlerhood: the toddler can use symbolic meaning and starts to experiment language, aided by memory and imagination. However, the toddler’s thinking is barely logical and egocentric. Also, self-control is not completely functional

2) Early Childhood: interest in others, fantasies, development of responsibility

3) Childhood: systematic manipulation of symbols associated with concrete objects. Operational thinking bypasses ego-centrism and improves reversibility

4) Adolescence: formation of the adult social role

These two sets are not independent: as the state of an object or person depends on their transformations, figurative intelligence is a product of operative intelligence, whose active and constructive processes allow building up understanding, assimilation, accommodation and, eventually, models of the whole world. Children learn to act on transformations (operative intelligence), and to attach a meaning - the state of an object - to transformations (figurative intelligence). Also, single actions tend to develop in systems whose cohesion leads to progressively higher levels of functioning, less errors and inclusive of more complex aspects of the world. In other words, the human actively builds their models of the world.

The process described above is domain-general: cognitive maturation occurs concurrently across different levels of knowledge. However, modern cognitive science beyond Piaget has mostly set aside the idea of a domain general mechanism, and neatly binds up complexity into domains of specificity. In other words, two mechanisms subtending walking and counting numbers are not simply qualitatively different, but serve evolutionary specified operational needs that require content specific information processing.

One example of a domain-specific account is the nativist and evolutionary psychological framework, that assumes a series of “core knowledge” that infants are equipped with. This vision implies that the development of different cognitive faculties is rather independent and occurs at different times - like real modularity.

More recently, the domain-general approach has been revised into a dynamic system approach - stating that specific-domain knowledge derives from the smooth integration of knowledge - a topic for my next post!